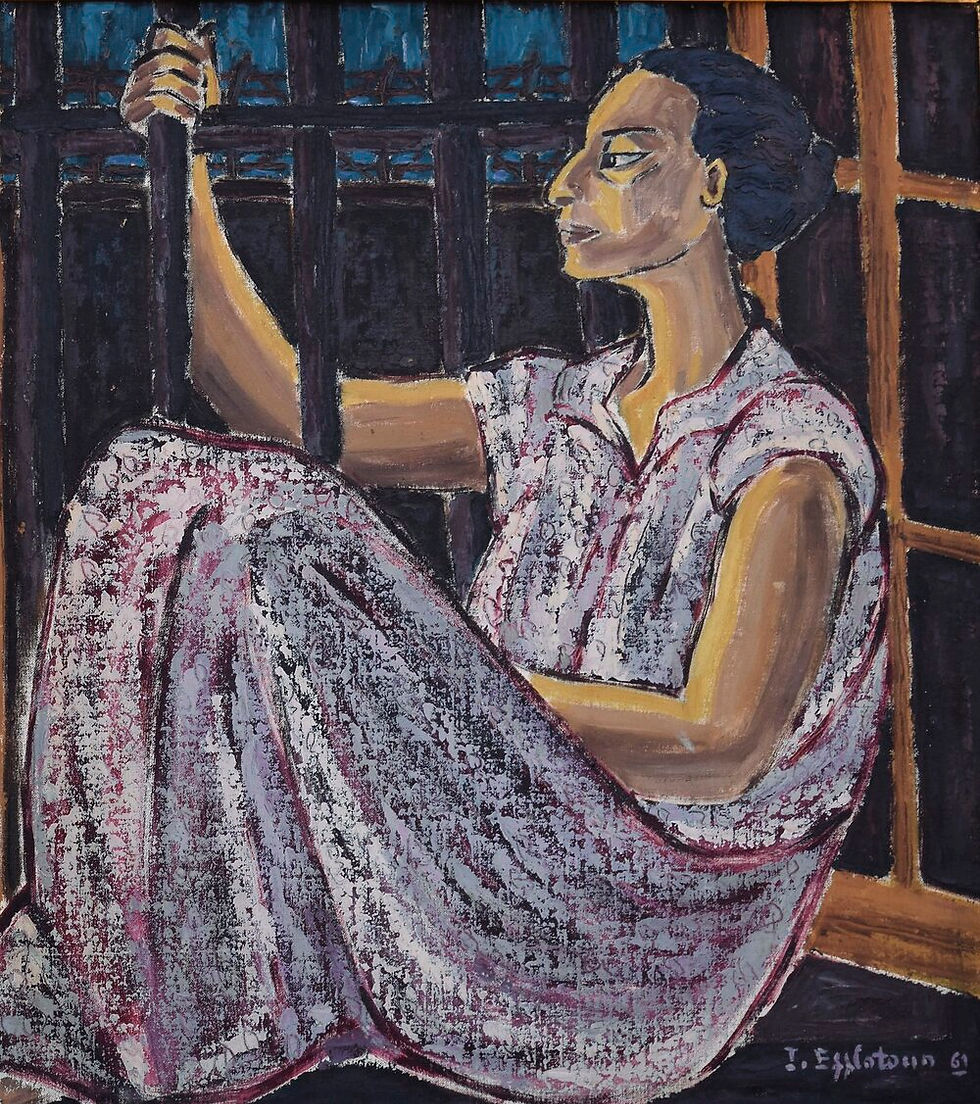

'Untitled' (Woman Prisoner)

- Suzanne Muna

- Jul 1, 2020

- 6 min read

'Untitled' (Woman Prisoner)

1961

Inji Efflatoun

Oil on canvas

Dimensions unknown

Private collection

Behind the Prison Walls

In Efflatoun’s painting (one of a series), a female prisoner in a long, pale purple dress sits in the corner of a barred room. Beyond the cell's bars lie the prison walls topped by spikes and the dusky night sky. The prisoner sits with knees drawn up, her dress is a flowing curve across her body. She is almost fully self contained within the cell, but for one arm wrapped around the bars, both escaping and holding on.

There is a resonance between Efflatoun’s work and the art of Van Gogh and Edvard Munch. She favours a primitive style, distinct forms with bold outlines; flattened planes of expressively covered surfaces.

It is a direct and accessible image, painted with the honesty of personal experience whilst Efflatoun was a political prisoner (1959-63).

In the image, the incarcerated woman's dark wavy hair is pulled back into a bun, exposing her face in profile to the viewer. What makes this picture particularly poignant, indeed slightly haunting, is her distant and wistful expression. In this series, there is a sense that Efflatoun identified closely with her sitters. The work is untitled, and could be a self-portrait.

Inji Efflatoun (1924-1989)

Efflatoun was born to a landowning Muslim family in Cairo, Egypt. Her background was comfortable, petty bourgeois, and traditional, but her mother was not. Instead, she provided a young Efflatoun with a model of female independence. She divorced Efflatoun’s father after just four years of marriage, launched a business, and became the first Egyptian woman to open a fashion shop, run a clothing factory, and travel abroad without male escort. This broke with class and gender expectations which dictated that she should be at home and dependent on male relatives both economically and for movement.

In the political sphere, the demand for greater gender equality was already being raised by the time of Efflatoun’s birth. In 1923, Huda Shaarawi had caused a public shockwave by removing her veil in protest at male privilege. Shaarawi went on to co-found the Egyptian Feminist Union which included amongst its objectives full access to education for girls. Such women forged a path for activists like Efflatoun to follow and extended.

Despite her Muslim background, Efflatoun’s mother decided to send her daughters to a Catholic boarding school. It was a rude awakening for a young girl raised in financial comfort and with liberal freedoms. She now witnessed the poverty and deprivation suffered by the school’s nuns, and was subjected to regimentation and restrictions. She later described the school as her first prison, giving the incarceration paintings an extra resonance.

As well as her lifelong love of artistic expression, Efflatoun was an eager student of history. She was fascinated by the philosophy of the French Revolution and Napoleon’s unsuccessful campaign in the region (1798–1801), which left its mark on the country. Initially, she pursued anarchist politics, but moved towards Marxism as she matured.

In her teens, Efflatoun acknowledged that her life had been relatively metropolitan and privileged. She had travelled frequently to France with her mother. But offered the opportunity to study art in France, she eventually turned it down preferring to explore the more remote and rural parts of Egypt to experience first-hand the lives of farm workers and labourers.

“With five or ten years of Parisian study, I would be a better artist but I would know nothing about my country.”

Art as Political Instrument

The struggles of the poorer classes drew Efflatoun increasingly toward political activism. An active member of the Communist Party, she wrote pamphlets and helped organise a variety of committees and conferences on the need to liberate both class and gender. She agitated for world peace, and promoted the role of art as an essential weapon in this battle.

Efflatoun learnt the power of art to galvanise popular opinion. In 1951 she painted the funeral procession of victims from the bitter struggle to end Britain’s control over Suez, an event which had profound political and economic consequences in both countries. She titled the piece “We Cannot Forget” and says of it:

“’We Cannot Forget’, played its role in expressing the popular sentiment by honouring the victims of anti-British political activity. My exhibit became like a demonstration … a political instrument.”

The image was adopted by the movement and widely used on propaganda. It became an icon for protestors and activists, but the notoriety began to draw Efflatoun to the state police’s attention, an unwelcome development in an increasingly oppressive regime. Despite a period in hiding, Efflatoun was eventually arrested in 1959 and indefinitely detained alongside twenty-five other women. They were the first Egyptian female political prisoners of the modern era. Efflatoun served in prison for more than four years, painting throughout.

The Battle for Egypt

Egypt’s riches had for centuries made it a strategic beacon for empire builders, including the Romans, Ottomans, French and British. It was a British protectorate with a puppet monarch between 1915 and 1922, after which it was independently ruled by the king. In 1952 a popular uprising finally overthrew the monarchy altogether and led to the rise of military rule under General Gamal Abdel Nasser.

In the early years of his rule, Nasser introduced progressive and populist reforms, including the nationalisation of the Suez Canal, free education for girls as well as boys, and women’s suffrage. But increasingly Nasser tightened controls whilst pursuing his pan-Arabian nationalist vision.

The question of Egyptian and pan-Arabian nationalism versus a more essentially internationalist character of true socialism was a recurring tension within the Left in Egypt. Indeed, in the early days of the coup, the Communist parties generally supported Nasser and the ‘Revolutionary Command Council’. Not surprisingly given the geographic proximity and its recent partition, the question of Palestine / Israel was also highly contentious. These and a multiplicity of other disputes were never satisfactorily resolved, and the two primary Communist wings in existence at the time dissolved in 1965, not long after Efflatoun’s release from jail. Nonetheless she remained politically active for the rest of her life.

Legacy

Efflatoun’s prison paintings, including the ‘Untitled’ piece, were publicly exhibited soon after her release. They helped throw a spotlight on the plight of women in prison in Egypt in the 1950s. It is a spotlight that needs to be relit across the world.

In many countries, women are far more likely than men to suffer sexual violence alongside the other deprivations and traumas of incarceration. Even in the UK, according to the Prison Reform Trust (PRT) and other campaign groups, women are more likely to be given custodial sentences than men for an equivalent offence. Further, women are more likely to be the sole or primary carers of children, and separation from them (especially infants), can have long-term harmful effects on both mother and child.

The PRT reports that women

“account for over 19% of self harm incidents, an indication of the traumatic impact of imprisonment on many”.

Yet because women form less than 5% of the prison population, they are often out of both the eye and mind of the public.

The imprisonment of women looks even more unjust when the reasons for incarceration are investigated. A detailed report from the US noted that

“Many of the violent crimes committed by women are against a spouse, ex-spouse, or partner, and the women committing such crimes are likely to report having been physically and/or sexually abused, often by the person they assaulted.”

(Gendered Justice).

These findings were echoed in Britain by the PRT.

The women in Efflatoun's prison series are, appropriately, unnamed, and unidentifiable; their anonymity is underscored in this untitled piece. Such is the invisibility of women prisoners across the world. It is time for change.

Greater resources for the prevention of domestic violence, and improvements to the support available to victims, would surely be a more effective and immediate approach to these crimes.

In a more civilised world, there would be a fundamental shift in our approach to criminal justice. A system would be introduced that favoured addressing the causes of crime. It would use thoroughly researched evidence to create its policy instead of the media-pandering, often hysterical and institutionally discriminatory practices that are still far too common. It would safely and humanely isolate those who were a danger to society, properly fund services to prevent re-offending, and rehabilitate where possible.

1 July 2020

(c) Suzanne Muna

Further Reading

Comments